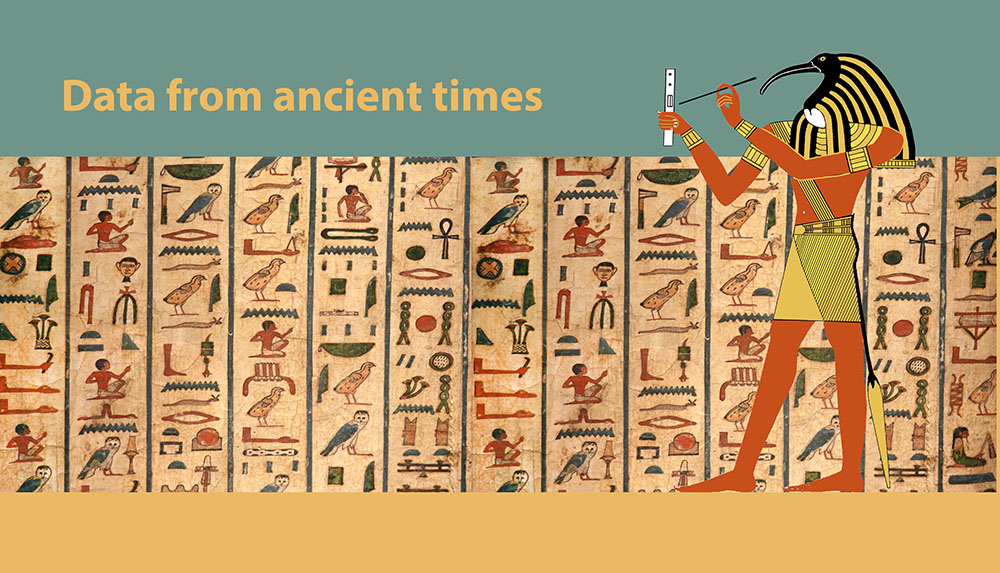

Data from ancient times

Medu netjer is what the Egyptians called their hieroglyphs, ‘divine words’. They were convinced that the hieroglyphs in temples and tombs contained divine wisdom. Thoth, the god of wisdom, is said to have given them writing. Through writing, they were able to preserve their knowledge for later generations. But the deeper knowledge from ancient Egypt lies beyond words, hidden in stone, shrouded in myths and symbols. And yet, the hieroglyphs themselves sometimes contain deeper knowledge.

Mysterious signs

Hieroglyphs are also data. Data from antiquity, data from the distant past. Hieroglyphs have always fascinated people. For a long time, no one could read them. In the last centuries of ancient Egypt, hieroglyphs were increasingly forgotten. The last hieroglyphs were written on a wall on the island of Philae in 394 AD. After that, there was no one left who could read the mysterious signs for a long time.

Over time, interest in ancient Egypt grew. The impressive buildings and beautiful sculptures appealed to the imagination. Temple walls were covered in hieroglyphs. But what exactly was written there? Did they hide secrets? Anyone who wanted to know more had to be patient, because the hieroglyphs were not deciphered until 1822.

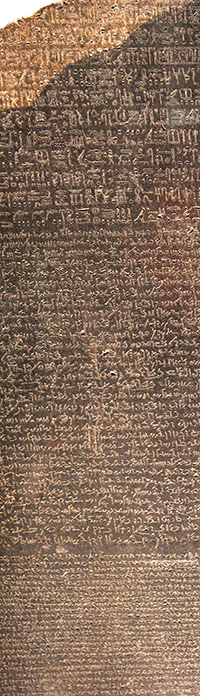

An important key to this decipherment was the Rosetta Stone. On this stone, the same text is chiseled in three languages: hieroglyphs, demotic (an ancient Egyptian cursive script) and Greek. And the linguists could read this last language. Although several people contributed valuable pieces of the puzzle that led to the decipherment, it was ultimately the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion who managed to solve the riddle of the script.

Scientists were finally able to read the characters. But the texts they found in tombs and temples turned out to be full of riddles; seemingly incomprehensible fragments of text without a logical order. For example, in the Book of the Dead, the Egyptian says that he ‘cackles like a goose’ and a few sentences later ‘stretchs out his wings like a falcon’ and then firmly asserts that he ‘is a lotus’. What were the scholars supposed to do with that? Was there more to these enigmatic texts? The ancient Greeks spoke with awe about the knowledge of the Egyptians. Many great Greek philosophers are said to have studied in Egypt. Plato had been there and Pythagoras is also said to have gained his insights in Egypt. If they studied there, then surely these strange texts must mean more?

Fig. 2 Detail of the Rosetta Stone with hieroglyphs at the top, demotic script below and Greek at the bottom. British Museum London. (photo Corina Zuiderduin)

Fig. 3 An Egyptian scribe with a papyrus sheet on his lap. In his hand he holds an imaginary reed pen. National Museum of Antiquities. (photo Corina Zuiderduin)

Hidden knowledge

The Egyptians wrote down many types of knowledge, from astronomy and mathematics to medical knowledge. But also texts about the origin of life, about what happens after death, about how to create a better fate, about paradise and about how to become divine. The ethical side of these texts is always written down in clear words, so that everyone can understand them. Another part of this knowledge is hidden in myths and symbols.

Hieroglyphs are also symbols. They were not only used as sound signs to write texts on temple walls and papyri, but also on all kinds of other objects such as statues, cabinets, jewelry and spoons. They were sometimes so closely connected to the objects on which they are written that they are part of the object.

Hieroglyphs

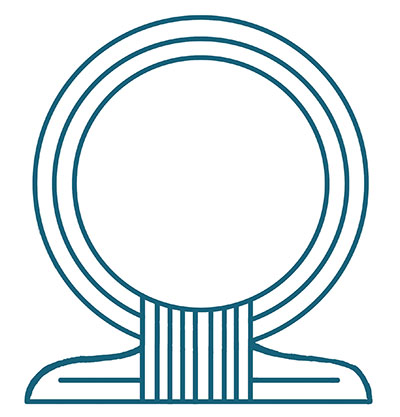

Hieroglyphs consist of stylized drawings of objects, plants, animals and people. An Egyptian scribe therefore had to be good at drawing and it is therefore not surprising that the Egyptian word for ‘writing’ is the same as for ‘drawing’. Sometimes hieroglyphs are works of art in themselves (image 1). Moreover, a scribe not only provided the text, but usually also the accompanying illustrations in, for example, books of the dead. Hieroglyphs were written in different directions. Some texts run from top to bottom. Others, like our script, can be read from left to right and still others can be read from right to left. There are no texts in ancient Egypt that you have to read from bottom to top.

It is not difficult to determine whether you should read a text from left to right or from right to left. If the figures in the hieroglyphs look to the left, you read from left to right. If they look to the right, you read in the opposite direction. You always read towards the faces.

It often happens that part of a text line runs from left to right and another part of the same line from right to left. Image 4 shows hieroglyphs on an ebony chest of Tutankhamun. The text starts in the middle and from there the left part of the text runs from right to left and the right part of the line from left to right. In this way, the hieroglyphs give a nice symmetrical image, while the text on the left and right is not exactly the same.

It also occurs that when two people or gods are depicted opposite each other, the text for one figure runs from left to right and the text for the other figure runs from right to left. This not only creates symmetry in the representation, but also reinforces the idea of mutual exchange of thoughts or words between the figures. The Egyptians do not use periods at the end of a sentence or commas. They do not even leave a space after a word. All words and sentences run one after the other. And yet a trained reader can recognize where a word ends and where a new word begins.

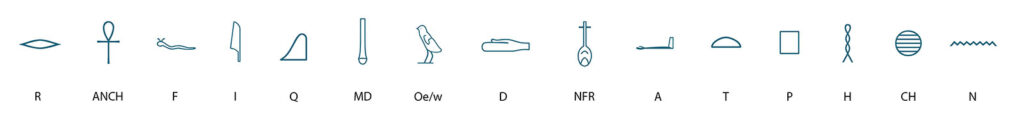

The letters

Egyptian script consists only of consonants. Vowels were not written down. Because words consisting only of consonants are difficult to pronounce, Egyptologists place the letter ‘e’ between the consonants. The word nfr -‘beautiful’ for example, is then pronounced as nefer. But how the words were actually pronounced, what the actual vowels were, is unknown.

Egyptian scribes and sculptors made sure that words were nicely placed in blocks. The letters of a word are not only behind each other as with us, but partly also above each other in the same word (Image 6).

Sounds and symbols

Hieroglyphs consist of two types of signs: sound signs and symbols. Sound signs represent a sound, just like our letters in the alphabet. Some hieroglyphs represent one sound, others two sounds and there are also sound signs that represent three sounds. We also know the single and double sound signs in our script. All letters of our alphabet represent one sound, except for the letter x which represents two sounds.

Hieroglyphs also consist partly of symbols. Many of these symbols are determinatives. A determinative is a symbol that is placed after a word. Because the Egyptians did not write vowels, it was not always clear which word was meant. A determinative then gives an indication of the meaning. For example, the Egyptians drew an eye after words that have to do with looking or seeing (image 7). They placed a human figure with his hand by his mouth after words that have to do with everything you do with your mouth, such as eating, drinking and talking (image 8). Words that have to do with walking or moving were provided with two walking legs at the end of the word (image 9). For words that express an opposite direction of moving, such as going back or turning around, the Egyptians drew the walking legs in the opposite direction (image 10).

Fig. 6 Spelling for the word ankh – ‘life’. Egyptians were flexible with their script. Egyptian words can often be written in different ways, for example in full as here, or abbreviated (Fig. 5A). This makes hieroglyphs playful and creative, while at the same time they are always neatly arranged. Words were often arranged in blocks. In this way, the symbols of a word together form a visually attractive composition

Two spellings for ‘to see’, peter.

Fig. 11 A The sound ‘r’. Some hieroglyphs can be both a sound sign and a symbol. The letter r, for example, is written by a stylized mouth. But this sign can also mean a ‘mouth’ itself. In the latter case, a vertical line usually follows (Fig. 11B).

Abstract

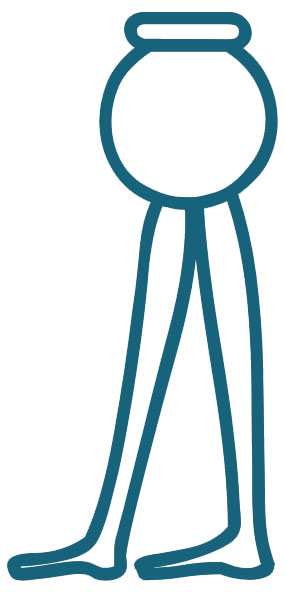

But what did the Egyptians do with an abstract word? How did they represent such a word? They had a solution for that too. At the end of an abstract word they drew a papyrus roll. This expresses that it is a word that you cannot draw, because it is abstract, but you can write it down (image 12).

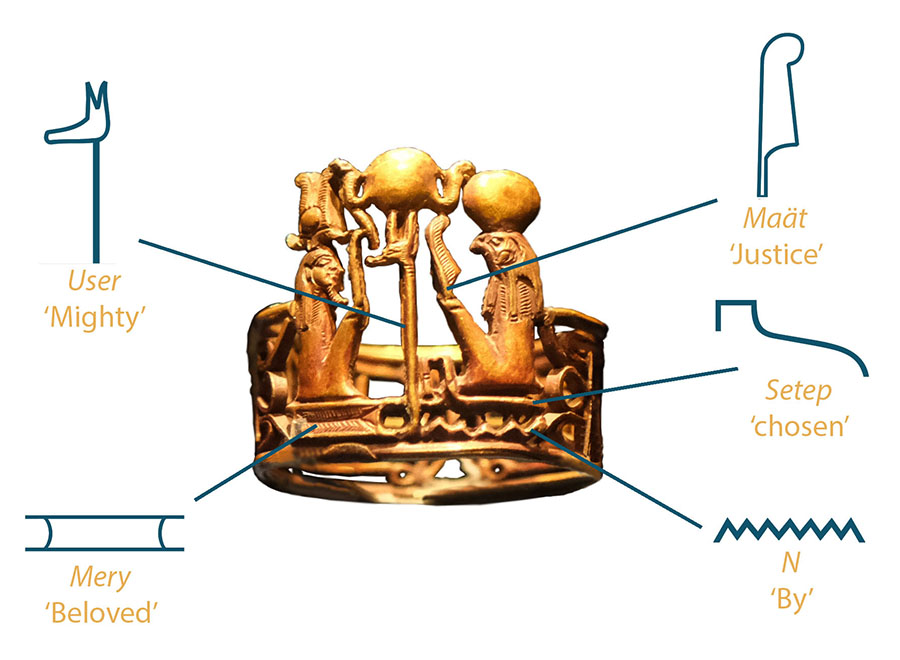

Sometimes hieroglyphs are so closely connected to the object they are written on that the object itself consists almost entirely of hieroglyphs. You can sometimes read objects literally (images 13 and 17).

Fig. 13 In this openwork gold ring, Amun (left) and the sun god Ra (right) sit opposite each other. The whole simultaneously forms the throne name of Ramses II: User-Ma’at-Ra, Setep-en-Ra-mery-Amun. Translated, his name means ‘the justice of Ra is mighty; the one chosen by Ra, beloved by Amun.’ Egyptian Museum Cairo. (photo Corina Zuiderduin)

Fig. 14 No one knows how hieroglyphs originated. Around 3100 BC we find the first hieroglyphs. This bowl dates from the time before the first hieroglyphs appeared. The bowl has two feet and is reminiscent of the word ini – ‘bring’ which is written by a bowl on walking legs. Another word that can be recognized in it is the word wab, which means ‘pure’ and is written by a leg with a pot on it from which water flows. Ca. 3700-3450 BC. Metropolitan Museum New York. (photo Corina Zuiderduin).

Fig. 17 Wooden ritual spoon. The fish at the top is a symbol for the sun god. The sun god represents the deepest core of every being. This core is always part of the infinite All. National Museum of Antiquities Leiden. (photo RMO)

Eternal beauty

Hieroglyphs are often connected to myths. The ritual spoon in image 17 is not only beautiful to look at, but is full of hieroglyphs. A young woman stands between lotus flowers. On her head and in her hands she holds nefer signs. These three signs together form the word ‘beauty’. We also see two Horus eyes that can be read as ‘seeing’.

The Egyptian maker of this spoon cleverly used the curve of the spoon’s scoop to express something. The round bowl represents the primeval water, the source from which all living beings originate and to which they return. According to the Egyptians, this source is an eternal and infinite principle of life, an endless field of consciousness. In the middle swims a tilapia fish, a symbol of the sun god. A tilapia keeps its eggs in its mouth to spit them out as soon as the young fish are born. The fish then regularly swim back into its mouth to emerge again shortly afterwards. The Egyptians therefore found the tilapia a very suitable symbol to express the cyclical unfolding of beings and their return to the All. In this spoon, the tilapia does not spit out fish, but lotus flowers to further emphasize the symbolism. According to the myths, a lotus flower also represents the origin of life and the return to unity. It also represents that you can once again become aware of this unity of which you are always a part.

The rim of the bowl is formed by a shen ring, the symbol for eternal time in which all beings emerge in cycles. In the corners are two frogs, symbols for birth.

Nefer

Hieroglyphs themselves sometimes express a deeper meaning. The hieroglyph for ‘good’ and ‘beautiful’, for example, consists of a windpipe that ends in a heart (image 19). The Egyptians knew the human body well and knew that the windpipe is not connected to the heart. They must have had a reason to express this in their sign for ‘beautiful’ and ‘good’.

In ancient Egypt, ‘beautiful’ mainly refers to inner beauty. The Egyptians considered people with good character beautiful. Someone with a beautiful character does everything in harmony with other beings, with the inner law of nature, with Maät. He lives and acts from his heart. According to the Egyptians, the heart is the seat of the inner god and is connected to love and wisdom.

Whoever spoke from his heart was honest and sincere and whoever lived (breathed) from his heart expresses the divine. There are various statements in which the Egyptian says that he lives (breathes) or speaks from his heart.

‘I live through Truth (Maät) in which I exist,’ says the Egyptian. ‘I am Horus who is in hearts. I live and speak from my heart.’ [1]

Horus represents the higher part of consciousness, that part in man that realizes the unity and connection with other beings and that therefore naturally does everything according to this unity.

Fig. 20 This necklace consists of golden nefer signs. Palm leaf motifs hang at the bottom. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (photo Corina Zuiderduin)

[1] Book of the Dead 29A

This article is an adaptation of an article that appeared in Bresmagazine 350 january/februari 2025 and on the book het Mooie Westen, mythen en symbolen in Egypte (2019).

Copyright text and photos: Corina Zuiderduin